I recently attended an outdoor music festival with my daughter, as her “birthday present.” I still can’t believe I agreed to go.

It required flying to a (relatively) distant location, staying in a hotel, and standing / walking in extremely close proximity to thousands of people for hours, on two separate days. Not exactly my favorite type of experience. But my daughter really — desperately — wanted to go; the festival featured several of her favorite bands. And the only way she could was if I accompanied her. (My wife hates massive public events even more than I do. So she was not an option.)

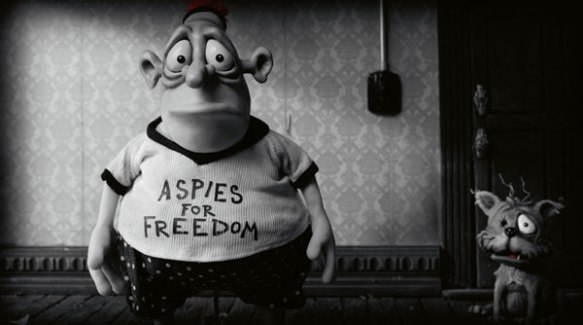

If there’s an experience that exemplifies the challenges of understanding neurotypical social interactions, it’s the massive outdoor event. And this one in particular was mostly populated by adolescents and twenty-somethings, who engage in lots of “rituals” that are too varied and fact-specific to be simply mimicked.

But lately I’ve been feeling more comfortable with interaction at large events. I’ve found I even enjoy parts of it (more on that later).

For example, when I first entered the music festival, a stranger held out his fist as I passed by, and I actually recognized it, albeit slower than most, as a request for a fist-bump. So I obliged. My daughter was bemused: why would a 20-something want to fist-bump her (old) father? But at least she didn’t cover her eyes or look away — you know, the “I can’t believe my father just did something so embarrassing” look. I think she might have even been proud. (But just so the record is clear, the fist-bump was more of an anomaly; the next day, when an intoxicated older woman offered me a bottle of beer, I did not accept; taking a drink from a stranger — and beer no less, which I despise — would be going too far.)

It was actually liberating, in a sense, to be at the festival. By deciding to attend, I had necessarily made a decision to challenge some of my biggest anxieties head-on, facing my fears, the same way someone with a fear of heights (another fear I have) might stand precariously on the edge of a cliff, looking down. (But I would NEVER do that.)

In fact, it was even worse (and therefore better?) from an anxiety standpoint, than I anticipated. It had rained heavily for days before the event, which meant large sections of the venue were covered in thick goopy mud. To approach some of the stages, you had to submerse your shoes in a murky brown paste. In case you think I’m exaggerating:

I wouldn’t say I conquered any fears; even at the concert, I still made efforts to maximize my personal space and minimize the degree and frequency of social interaction. But still, I participated in an activity outside of my comfort zone. And I found that I enjoyed being surrounded by people (to a certain extent) and I enjoyed the spontaneity (again, to a certain extent).

At 40, I’m so much more comfortable with myself, with my “own skin” as some people say, than when I was younger. That made me happy. On the other hand, being at the concert and seeing so many people in the 16-24 age group brought back memories, many of them painful, of growing up and desperately trying to fit in, to be one of the popular kids. And of outdoor concerts.

I still vividly remember the time I went to a 4th of July day-long outdoor concert the summer between my junior and senior year of high school. I was attending an academic summer school, and even there I made few friends. I was so miserable that I left the event just before it got dark, just before the best part (the fireworks). As I walked to the subway station, everyone was moving in the direction toward the park, except me. It was a metaphor turned real.

Fast forward to the present: As a 40 year old accompanied by his tween daughter, I was now having a much more enjoyable experience at an outdoor concert than I did when I was younger (the age at which people are “supposed” to enjoy those events). It made me happy but was also a bitter irony; I guess it was bittersweet.

And I asked myself: Why was my experience better now? Why was it better at the time in my life when most people hate standing in the sun for hours surrounded by lots of noise and sweaty teenagers?

Perhaps the answer is life experience, a greater knowledge of how the world works and how to be happy in my “own skin.” Maybe it’s also partly that, unlike when I was younger, now I’m not trying so hard to be cool, to be accepted. It also helps to have a wife and daughter who help guide me — who, while they accept my quirks, also aren’t afraid to tell me when I’ve gone too far. And I guess I’m also more willing to take risks now that death’s doorstep is that much closer.

If I could speak to my younger self, the version of me who struggled so much, I would tell him to have his own style … but to choose it carefully and then fully embrace it, and not to worry whether it matches other people’s. I’d also tell him that life will get better; he just has to be patient. And that he should give outdoor musical festivals another try.

Incidentally, if you haven’t listened to songs by Vampire Weekend or Cage the Elephant, I highly recommend them. A good place to start with Vampire Weekend is Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa and Horchata. And for Cage the Elephant, I’d recommend Aberdeen and Shake Me Down. I tried to post a video clip from the festival but it was too large. If you want a sense of what it’s like to see Cage the Elephant live — they put on an amazing show — here’s a clip from a different music festival. Hope you enjoy!